Hearts in Camoflage

April 5, 2021

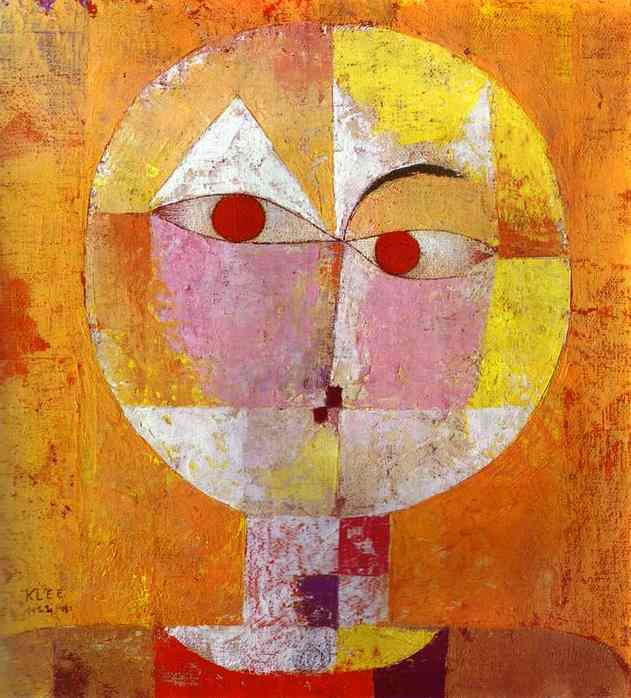

This is probably Paul Klee's most famous and popular painting. It has been widely distributed as posters and art prints. It has turned up on throw pillows, coffee mugs and T-shirts. And it has long been one of my all-time favorites as well. I've never tried to analyse why I like it so I thought I'd see if I could learn something by meditating on it now.

I never noticed the painting's title until now: Senecio or Head Of A Man Going Senile. Senecio, which means "old man" in Italian, apparently was a performance artist of the day, known for playing the Harlequin. Traditionally, the Harlequin is a trickster who delights in subverting the intentions of more serious and conventional characters. And, like the Harlequin, cognitive disease always does that. It undermines the predictability and self-perception of everyone touched by the affected individual’s presence.

I used to work with elderly people suffering with dementia ( we no longer say they are going senile). Our therapeutic activities aimed to keep patients safely engaged with their environment and social networks even as their interactive skills slipped away. I never thought this effort was a lost cause in spite of the inevitable declines.

I never thought of it as an exercise in futility even though I knew their future only held further loss: There was unremitting erosion of motor and verbal skill There was the certain loss of memory and knowledge of all the things they had ever seen and done. Worst, there was the forgetting of all the people they had loved. As I look at this painting now, I think I see in it the reason I found my work with this population far from futile. To me it was profoundly meaningful.

As individuals lose dominion over mind and body, their public persona is broken. Behavior becomes disorganized and they lose social graces. Their confused antics subvert our best-laid plans and we regard them as clownish and disruptive. They don't fit in any more. As old friends and family, we no longer recognize them as the persons we used to know so well. But...they are still there.

I think Klee's Head of an Old Man Going Senile gives a hint of the man behind the Harlequin persona.

As I gaze at the painting, noting the arrangement of shapes and colors, the mask seems to me to hold an expression of bafflement and uncertainty. The lopsided, dilated eyes, the pursed mouth are anxious and apprehensive.

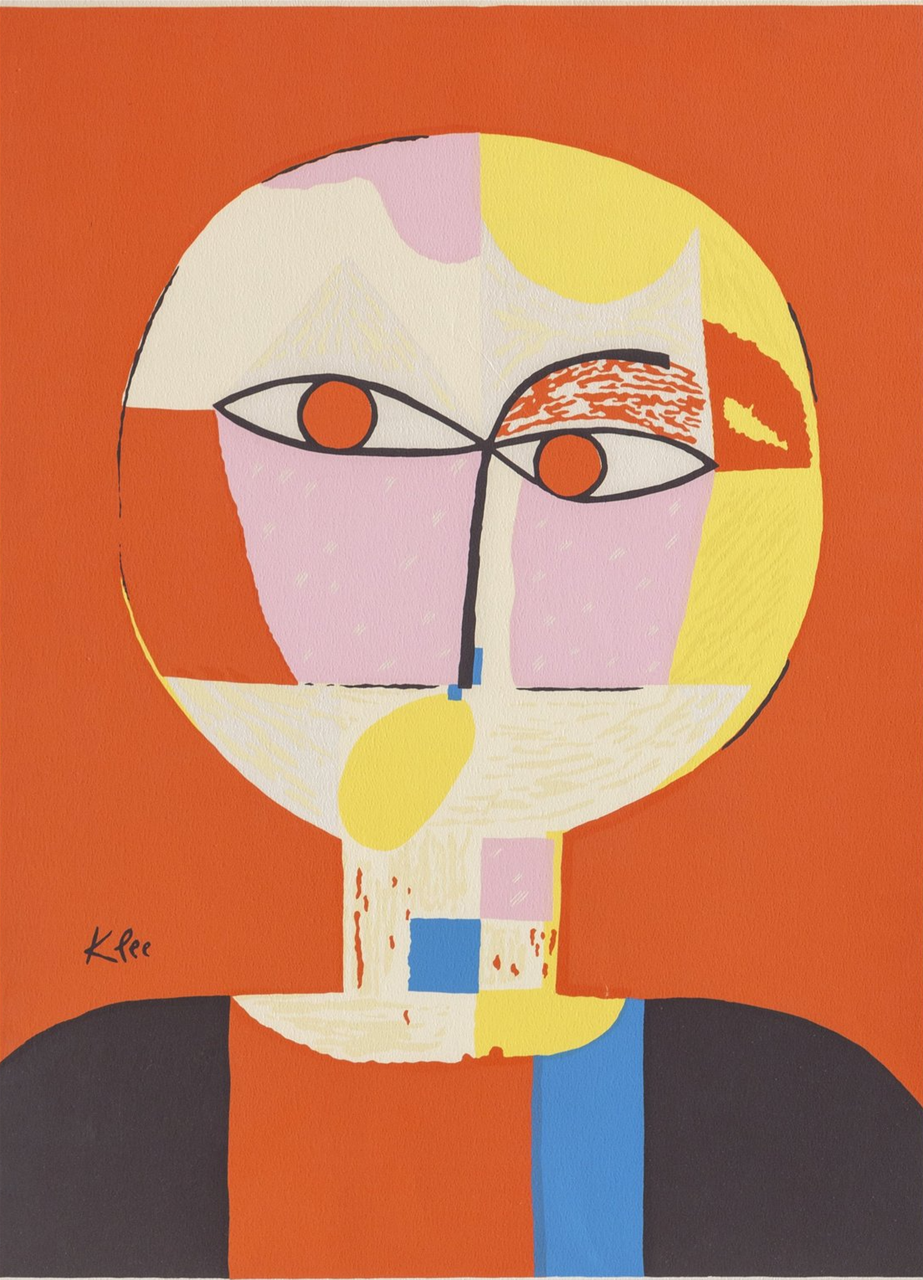

The longer I look the more a ghost-like figure emerges from behind the mask. The stylized interpretation from Ro galleries partially outlines the face inside the face. In Klee’s original it is mostly hidden--camouflaged by the larger pattern. But it is still there and I can't now un-see it.

And so it was with my confused elderly clients. The more their mental disease broke up all the patterns uniquely identifying an individual as John or Hester or Seamus, the more the person's core became visible. Finally it would dawn on me that I was now seeing the person inside the persona. Unable to navigate on their own but still whole in the heart’s deep abode where humor, faith, generosity and love spring eternal. If I was engaging with a ghost, it was a ghost who was literally "all heart". No lost cause here.

I have no idea whether Paul Klee had any of this in mind as he created this painting. I know in all my decades of admiring it, it never once occurred to me on any level. Now that it has, my appreciation for it has taken a quantum leap and I am glad that it has become such a huge presence in our popular culture.